Dull, lifeless sounding strings with little to no tone, and sustain that seems to die out almost immediately. This is no path to enjoyment nor grounds for a creative session. The outcome of your live performance or studio session could very well be at the behest of your strings.

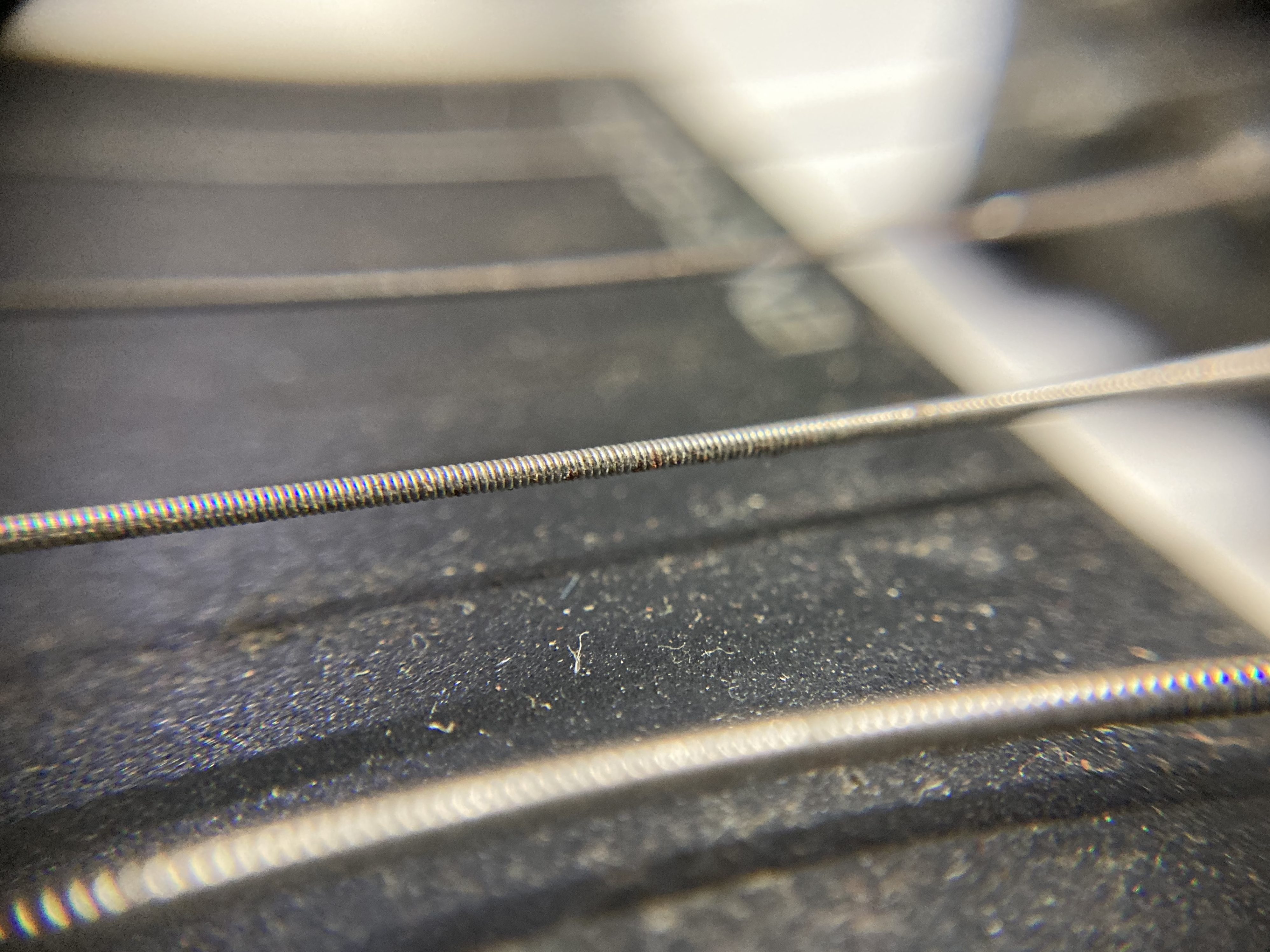

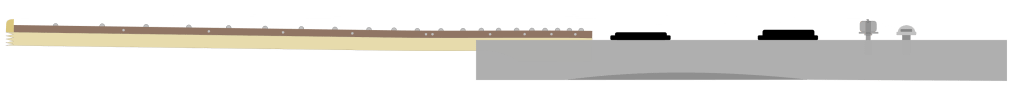

I recall the first time I changed my strings while in the midst of a practice session. My sound was uninspiring and I’ve had enough of adjusting my amp. My bedroom practice tone seemed to have faded yet nothing changed. I marked my amp face and pedal settings and started over but something had changed and it wasn’t my settings. Focusing back on my guitar I started to remember how often I had to unlock the nut on my second-hand Warlock with a licensed Floyd Rose bridge on it and adjusted the spring tension. I just thought the bridge didn’t stay put because it was cheap. I started examining the strings and noticed a lot of discoloration on the underside of the strings where they came in contact with the frets. I ran my fingers underneath the strings to wipe away the grime but I found that those areas felt raised and/or flat… and still blackened with grime. I looked around a little more; the sweat from my palm-muting has caused the strings to corrode between the bridge and the bridge pickup. I’m noticed a little more corrosion on the tops of the strings where I fret most. Celluloid and nylon shrapnel was embedded into the wound strings from my pick attack. These strings were looking beat!

The strings on this guitar have seen far better days. Regular playing habits like washing your hands before playing and wiping strings down after playing can extend string life.

The revelation…

I didn’t know anything about how long strings lasted but was wise enough to keep a few sets on hand, usually replacing individual strings when they broke. This time I clipped the old strings and installed a whole new set. Without the knowledge I have today, I didn’t pay enough attention to how the guitar sounded unplugged, but I noticed it immediately after plugging it back into my amp.

I seemed to have regained the sound that made me enjoy playing that no amount of amp adjustments could make up for. I adjusted all my amp and pedal settings back to my marks and was astonished: It was the strings! For a broke kid, the least expensive thing on my guitar was the only expense I could afford. This revelation had me paying much more attention to my strings from this point on.

Think about the path of your sound: you fret a note or chord and strike the strings. Forget about your amp or your pedalboard right now because everything happening before your ¼” jack is the foundation of your sound… and it could be in ruins! Your guitar, acoustic or electric, should have a quality sound to it before it’s even plugged in. Let’s set aside any contributing factors like the guitar’s electronics, hardware or its mechanical impedance for later articles; the strings are the fulcrum here.

Listen…

New strings sound brilliant. You can hear the fundamental note (the note you are intentionally playing) accompanied by harmonic overtones that make even single notes played sound full. The strings also sustain for a longer period of time. Playing chords brings this out even more. The guitar sounds full of life. After several hours of playing you can hear this start diminishing and the strings begin to sound a little less brilliant. It’s harder to notice over time if you’re only playing for short sessions and, perhaps if you’re just starting out, focused more on landing the notes. A gigging musician might even attribute their tonal despair some nights to the venue or perhaps components of your sound chain after the guitar. The fact is: Strings start losing their brightness after only a few hours of rigorous playing. I’ve personally noticed it during long writing and recording sessions and I believe any seasoned recording engineer would agree.

Studio Time…

While living in Los Angeles cutting my teeth as a guitar tech, I had the opportunity to moonlight on several recording sessions in studios across Hollywood. I was mostly just restringing and confirming the guitar was still intonated, only occasionally performing surgery. A great takeaway from these times was learning that record engineers hear, think, and discuss the sessions in frequencies. Music in the studios often discussed and dealt with in Hertz, not just keys or chord progressions. I was fascinated by their perception of music and how dedicated they were to achieving a quality source sound.

The engineers would be auditioning guitars the artists or studio had on hand and would request new strings almost on the same frequency of fresh coffee. They would also stop performances in the middle of a take because they could hear an acoustic guitar pre-amp rattling in the soundbox or the intonation on a bass going sharp up the fingerboard. Sometimes they’d walk right into the booth and strum the guitar themselves, returning to the room with the guitar in hand and a polite, “Hey Paul, could you throw some new strings on this?” These were engineers who make their living off of and stake their entire reputations on their interpretations of what sounds good. They know how crucial the sound at source is. The loss of overtones, tuning stability, and the overall tone of these guitars were at a point where “studio magic” couldn’t save the sessions without an immediate change to the guitar itself.

When my work for the moment was done and I knew I could come down from being a fly on the wall, I would ask the engineers what habits might be the most common to address when it came to recording guitarists and the responses were quite unanimous: if it wasn’t a request to have a tech come in and setup a guitar it was a blunt, “just change your f**king strings before you get here!” And right they are. I still ask this question to engineers I meet to this day and they haven’t changed scripts.

The life of a string….

So what is the decline of a string’s life like? Let’s examine a plain, unwound steel string first.

A plain guitar string is made of steel, a ferrous alloy containing iron, which makes it magnetic. Strings are much harder than most frets which, for most guitars on the market, are made of a nickel silver alloy. (Some frets are made from stainless steel or contain titanium, both more durable albeit more expensive. Still, many players and builders prefer traditional nickel silver frets.)

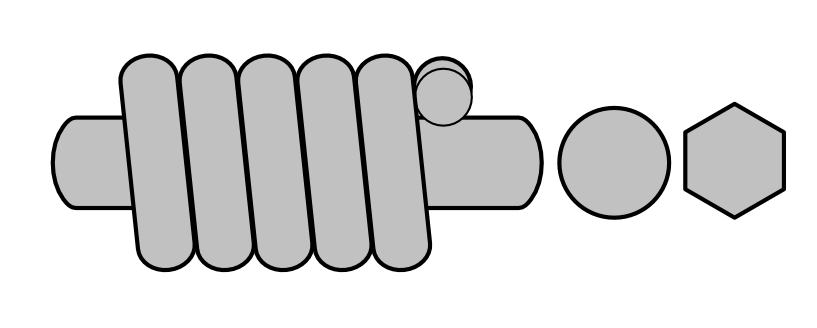

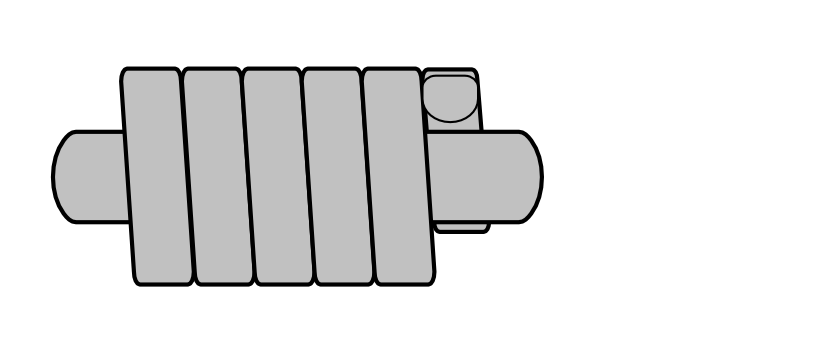

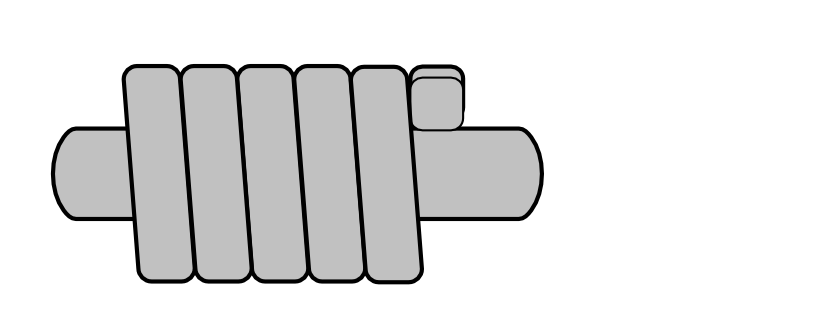

On wound strings, the steel core is wrapped in a variety of metals: nickel, bronze, even stainless steel. Wound strings are also available in several construction methods resulting in different tonal characteristics and feel. The most common materials acoustic and electric guitar strings are wrapped in are bronze and nickel, respectively. They will develop flat spots just as well, and often more prominently, as these materials are softer than the steel core.

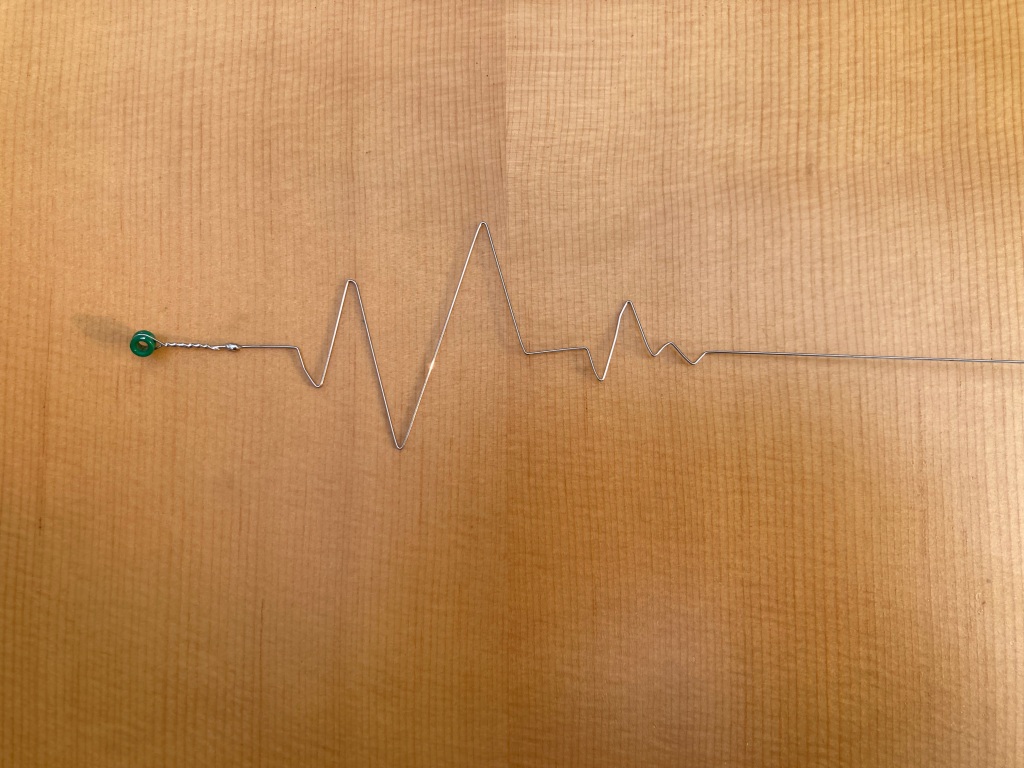

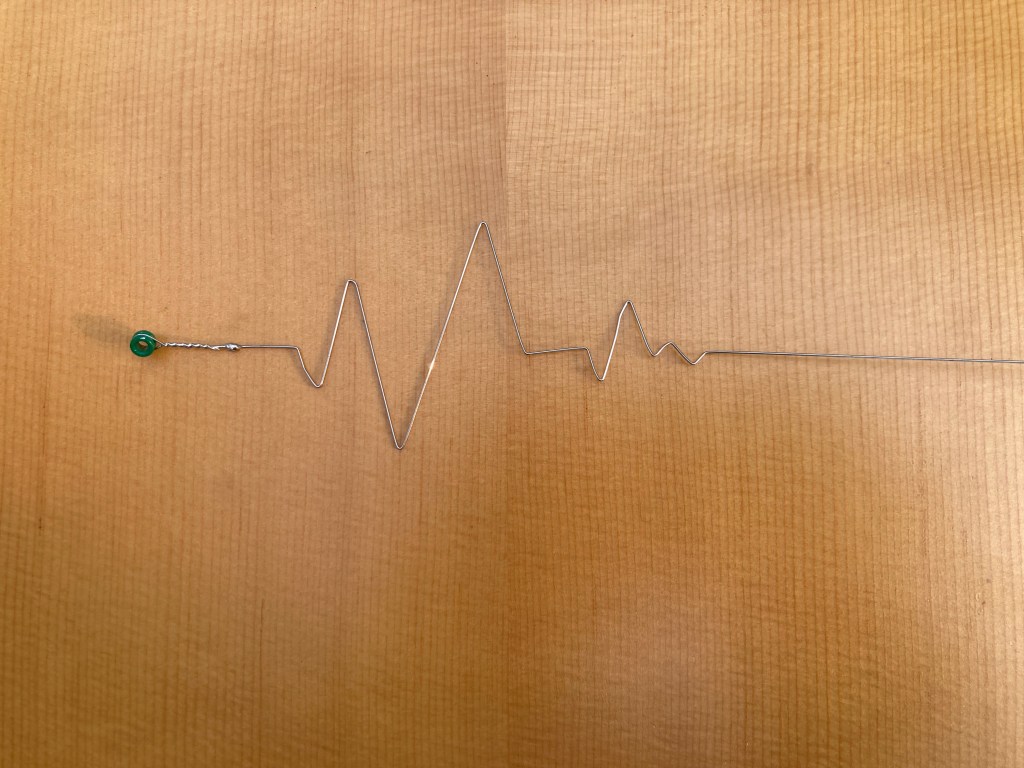

The point at which a string and fret contact are initially (given new strings and properly crowned frets) two round surfaces with minimal surface contact. As you fret and bend this note, the much harder steel string digs into and grinds away the fret, creating flat spots. But the damage isn’t just one-sided: your strings are developing flat spots where they contact the fret. The harder you fret, the faster the flat spots appear. The bigger the bends, the longer the wearing surface appears across the strings and frets.

Put it all together…

Now consider this happening on every string at every fret you play. These flat spots affect the way the strings vibrate too, leading to a loss of sustain, overtones, and unwelcome buzzing.

Another significant contributing factor to string death is the oils, dirt and sweat coming from our hands. Everything your hands go through build up on strings which become visually noticeable as dull and dark spots. Our sweat glands are not all created equally and I’ve seen this consistently from clients who are very sweaty (hey, they know it!) and bring their guitars to me for every string change. Some people have a slightly more acidic sweat than others and they’ll see corrosion build up quickly. All of this dirt, oil, and corrosion is accumulating on the strings and adding to the mass of the strings. It is noticeable and you’ve probably been aware of the effects.

Over time, as the strings take on this additional mass of, it requires you to tune the strings up more to achieve its pitch. This extra tension will start pulling on your neck more, lending to higher action and sharper notes across the fingerboard. If your guitar has a vintage or locking vibrato, you’ll notice your bridge sitting higher and your fine-tuners (if equipped) are maxed out . Your 10’s are almost starting to feel like 11’s. At this point, the strings sound so dismal that I’m baffled that anyone would still be playing on them, forgetting what the guitar sounded like before the strings hit rock bottom.

Make the change

It’s time to change your strings. For your tone’s concern and your instrument’s sake.

I’ve seen the darker, long term effects of prolonged string use. I’ve repaired dozens of acoustic guitars where the same set of strings (now completely rusty-brown) on a guitar for several years has played a significant role in pulling the bridge off of the top – often taking some of the topwood along with it. I’ve heard clients complain of a floating bridge that gradually gets higher until it’s painful to play higher on the neck. They’ve speculated on worn vibrato springs but this is the same phenomenon. A guitar equipped with vibrato won’t see the neck pull forward as much as it’s mounted bridge kin because the spring-tensioned bridge will lift as the strings start winning the tension battle on account of some dirty, sweaty hands.

You should replace, or have your strings replaced, when they lose their tone and trueness. You should be the judge of this and it only takes some quick observations: Look at your strings and listen to their sound. Listen to your guitar with a new set of strings on it before it’s even plugged in. In fact, make a recording on your phone or in your studio. Revisit this recording later by recording the same riffs or licks in the same manner. You could record these moments through your amp as well. You’ll be surprised how a few hours of constantly playing a set of strings can change in tone. You’ll probably notice some treble die-off first and a ghosting of overtones. Pay attention to the sustain of the notes as well.

If you’d like to learn how to change your strings yourself, or at least see how it’s done, stay tuned for my first blog in my upcoming DIY series!